One of the main concerns of independent media readers in Russia right now is related to propaganda in schools. This is indicated, for example, by the research conducted by Paper.

The Ministry of Education is introducing new tools of ideological control in schools – from compulsory flag-raising to the unified history textbook. Also, repression against individual students and teachers creates a general atmosphere of anxiety. However, little is known about how schools actually implement these new initiatives.

Paper asked four teachers from St. Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast to tell about how their work and the atmosphere in ordinary schools have changed in practice over the past year and a half. At the request of the interviewees, we have changed their names and do not disclose the schools where they work.

How the “Emphasis on Upbringing” is Implemented

Starting from September 1, 2023, hundreds of schools in St. Petersburg introduced principals’ advisors for “educational work”. In other regions, this position began to be introduced as early as 2021. At that time, the Minister of Education, Sergey Kravtsov, assured that advisors for educational work would not engage in ideological control but would focus on organizing extracurricular activities such as “sports events, theater and museum visits, and networking.”

However, in early 2023, the idea changed: Kravtsov clarified that advisors should carry out “information and instruction work” with students and teachers, as well as involve students in projects of children’s and youth organizations. A source cited by Kommersant also mentioned the Ministry of Education’s request for discussions with children on political topics, including protests.

As a result, after the first few weeks of the school year, teachers have a vague understanding of the role of educational advisors. According to four teachers interviewed by Paper, these employees do not participate in the educational process but work with students, homeroom teachers, and school facilitators.

Paper’s interviewees note a particular emphasis on upbringing in recent years. Teacher Irina tells that in the past, teachers spent extracurricular time on additional education, physical development of children, or creativity. Now, in primary school, one hour a week is dedicated to the new upbringing program called Orlyata, and in secondary school, time is allocated for career guidance. “Now it’s a mandatory subject once a week,” Irina says about her school in St. Petersburg.

Teacher Maria, who left a public school at the end of the previous school year due to a conflict with the principal, says that half of her time was devoted to educational work, but it was “not about patriotism but, for example, about conflict resolution, discussing one’s emotions.”

At the school where Maria worked, as well as at others, there was a national festival of creativity called “Russia, My Homeland,” which was the only activity that had an ideological nature. Until last year, there was no mandatory ideological curriculum according to Maria, but then “Conversations about Important Things” appeared.

How “Conversations about Important Things” are Held

Starting from September 1, 2022, in Russian schools from grades 1 to 11, a new lesson called “Conversations about Important Things” was introduced. Formally, these are extracurricular activities, but they are mandatory to attend, as emphasized by the Ministry of Education.

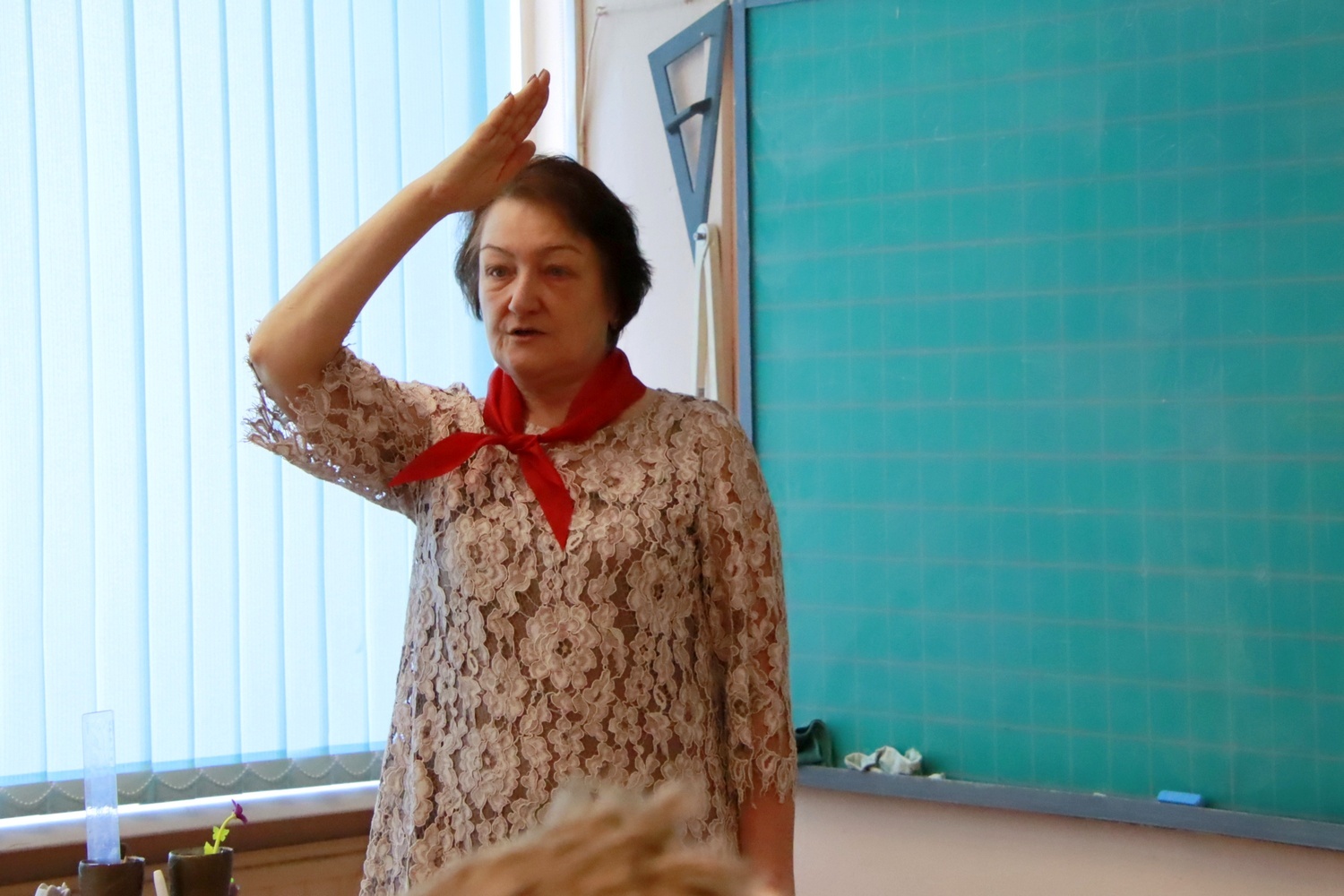

During the “Conversations about Important Things” class dedicated to the 100th birthday of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya on September 18, 2023. Photo: “School 324 of the Kurortny District of St. Petersburg.”

The general theme of “Conversations” is the history and culture of Russia and the country’s role in global processes. During the previous school year, some classes featured video lectures for all students on “combating Nazism in Ukraine” and “serving the motherland.” In St. Petersburg, there were reports of how certain teachers approvingly discussed the inclusion of Ukrainian regions into Russia. However, there are no mandatory lesson plans for each class – their content depends on the teachers.

What else do the Authorities Want to See in “Conversations about Important Things” ↓

What else do the Authorities Want to See in “Conversations about Important Things” ↓

In 2023, guidelines for these classes placed special emphasis on the themes of gratitude and heroism. They also explain what “traditional values” need to be instilled in students. It is stated that the classes should contribute to the “development of civil-patriotic feelings” among students.

According to the authors, “gratitude” should be expressed through actions, including service. The guidelines refer to parents as heroes, mention mother heroines and also describe participants in the “Special Military Operation” as heroes.

In the previous year, “Conversations about Important Things” were often conducted with the participation of celebrities who also touched on the topic of the army and the invasion of Ukraine. For example, monk Cyprian spoke about the sense of danger necessary in war but urged people to stand firm on the front lines. “God does not love the fearful,” added the clergyman.

Sergey Lavrov, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, praised children who sent drawings to the front line and teenagers who performed in places where Russian armed forces were stationed. Lavrov stated, “Children raised in this tradition and children who understand that there are sacred things will grow up true patriots.”

Most of the themes in “Conversations about Important Things” in their schools are not related to war and promoting patriotism, according to teachers interviewed by Paper.

For instance, as Anastasia mentioned, some “Conversations” focus on Russian cities. Additionally, as pointed out by teacher Irina, the topics of classes have included “red-letter days.”

Teacher Maria asserts that in the public school where she worked, nobody conducted “Conversations about Important Things,” and there were no consequences for anyone due to its absence.

How Patriotism is Cultivated in Schools

Starting from 2022, Russian schools also introduced the mandatory practice of beginning the school week with the raising of the flag and the playing of the national anthem. Irina, from a school in St. Petersburg, says that this top-down approach constitutes “patriotic education,” and it is limited to these actions.

Roman, a social studies teacher from a school in Leningrad Oblast, confirms that schools can easily fulfill imposed requirements as a formality without making significant changes to the educational process.

“In school, essentially the same things are happening as they were 20 years ago. From the outside, it may seem different, but that’s a cognitive error. You can think of the school as having several layers that sometimes work independently of each other. The first layer is education. The second, third, and fourth layers are related to upbringing, opportunistic factors, politics, and so on. All of these have their own KPIs.

“During the first two months of the war, nobody cared about school. It was only later that patriotic KPIs for children’s upbringing emerged. But in reality, all these KPIs are purely technical. It’s like when the system was going through digitization; they simply purchased computers. But how do you deal with upbringing? You need more patriotic events. And the reporting format is a photograph. I can take 10 photos in one day in different classes, and then spend a month reporting that I conducted these lessons.”

Anastasia agrees with Roman. According to her, there haven’t been any “super powerful” changes in the ideological role of the school, although she does see some patriotic events, such as lessons where children draw soldiers. “In general, it’s still the same as what we were told in school: soldiers are defenders. It’s not like you come to school, and it’s a military camp there.”

Irina adds that attempts to revive the pioneer movement in the school where she works have not found much resonance.

“Right now, they are trying to create the ‘Movement of the First’, and in our school, a very small percentage of students have joined it, and even those who have, are not interested in the idea but rather in the events that take place there.”

How “Special Military Operation” is Discussed in Schools

“Regarding the war, nobody openly discusses it in schools; it’s like a taboo subject. If someone’s parents are leaving for the war or, on the contrary, someone is coming to study from regions where the war is ongoing, no one openly talks about it”

As the teachers informed Paper, inviting military servicemen is not a common practice. “Special Military Operation” participants only came to the school where Maria worked, and she is unaware of what they discussed with the children.

According to Irina, the school administration recommended teachers not to discuss “Special Military Operation” and related events with the children, and the educators followed this advice. “We are very careful in identifying children whose parents have been mobilized to provide them with government support: food, special privileges,” she adds. As for events involving the military, there was only one concert at their school, where former students – “Special Military Operation” participants were invited, and discussing the war there was strictly prohibited.

Roman also shared his experience of avoiding the topic of war in their school.

“Regarding the war, nobody openly discusses it in schools; it’s like a taboo subject. If someone’s parents are leaving for the war or, on the contrary, someone is coming to study from regions where the war is ongoing, no one openly talks about it”

How Censorship and Self-Censorship Work

According to Roman, not only is the war hushed up in school, but also anything related to politics. The teacher notes that the space for dialogue in schools has almost disappeared after the poisoning of Alexei Navalny, protests in his support, and the intensification of repression. “History lessons have ceased to be a place for discussion – now you think several times before presenting an alternative point of view. The narrowing of the space for dialogue, in general, undermines everyone who teaches humanities,” he adds.

Some schools attempt to control students’ expressions, even in their personal social media accounts. Since March 2022, there have been reports that school administrations force teachers to monitor students’ social media for “destructive content” and “denial of family values.”

Maria, who resigned from a public school, shared this practice with Paper – her former colleagues told her that they were required to check students’ social media accounts. According to Maria, this control measure doesn’t work because teachers don’t have the time to figure out whose page belongs to whom, as students can use fake names or completely lock their profiles from strangers.

How the Unified Educational Program Standard is Implemented in Schools

Starting from September 1, 2023, new “Federal Basic Educational Programs” for all subjects have been implemented in all Russian schools. This means that there is now a nationwide, standardized program for each subject that teachers must adhere to, along with uniform textbooks.

“Schools are transitioning to a new educational standard, new working programs. Currently, they are also standardizing textbooks: whereas in the past, you could choose a course, now there is a strict schedule,” says Irina, a teacher from a school in St. Petersburg.

However, the distribution of the textbooks to all schools has not been completed yet, as Paper has found out. “Last year, in St. Petersburg, they transitioned the first and fifth grades to the new general education standard, and they studied for some time without textbooks. In 2023, they transitioned all students from the first to the seventh grade, as well as the tenth grade,” Irina describes.

She claims that new textbooks for various subjects have not yet arrived at their school. Her statement is partially supported by reports from TASS stating that history textbooks for 11th grade only became available in all Russian schools on September 18. “The unified Federal State Educational Standard is a good idea, but the rush is questionable,” Irina says.

Maria adds that changes in standards and programs have led to a reduction in the number of English language classes in schools, which has forced some teachers to retrain.

How the Atmosphere in Schools Affects Children

Psychologist Alexander Kolmanovsky, in a conversation with Paper, warned about the potential consequences of growing up in conditions of war and propaganda.

“The first thing is, in a manner of speaking, a disrupted psychological pattern. It’s impossible to maintain the existing narrative with complete inner clarity, so people develop double moral standards. There is more cynicism <…>

“Secondly, there is a genuinely heightened level of aggression. Aggressive individuals are not just unpleasant; it’s not just bad that they can explode at any moment. Aggressive individuals perform worse, think less clearly, and have worse relationships. They harm both those around them and themselves.”

Three out of four of Paper interviewees do not notice any changes in the state or moods of students over the past year and a half.

Teacher Irina explains that in February 2022, the school was tense because both teachers and students divided into different camps: some were for the war, some were against it, and some remained neutral. “The majority chose neutrality because not much depends on us anyway,” she explains.

According to Irina, things have calmed down now, and some students have become involved in organizing aid collections for the military: “Some have relatives there, and we also have graduates there.” She mentions that teachers themselves were prohibited from organizing collections and demanding money from students.

“I don’t see significant changes in their emotional state – teenagers were teenagers, and they remain so,” says Roman, a social studies teacher. The only thing that seems new to him is that “kids are thinking about leaving the country.”

Roman believes that there hasn’t been a significant increase in overt displays of militarism among students lately. He recalls that there have always been “activists” in schools. In his time, they were “zarnichniki” who went to civil defense teacher and disassembled automatic rifles. Nowadays, there are students who wear military uniforms and berets to patriotic events, raise flags, and march in formation. They represent a small percentage of students, but because of photos on the internet, it creates the impression that there are many of them, Roman believes.

He also mentions that in their school, there haven’t been grassroots initiatives related to the war, and this topic doesn’t elicit strong emotions.

How the Composition of Students has Changed

The mass emigration of Russians has had a limited impact on the four schools mentioned by the teachers who spoke to Paper.

“There are no mass departures; a few families have left,” says Irina. The same situation exists in the school where Roman works.

In Irina’s school, there are three students from “new regions.” Other teachers also mentioned a small number of refugees, but no one noted that this topic was being discussed prominently.

According to the teachers interviewed by Paper, they believe that war and propaganda do not significantly interfere with the educational process. However, based on their accounts, teachers and students are forced to adapt to unspoken restrictions, learn to keep their opinions to themselves, and perceive imposed conventionalism as a meaningless imitation of activity.